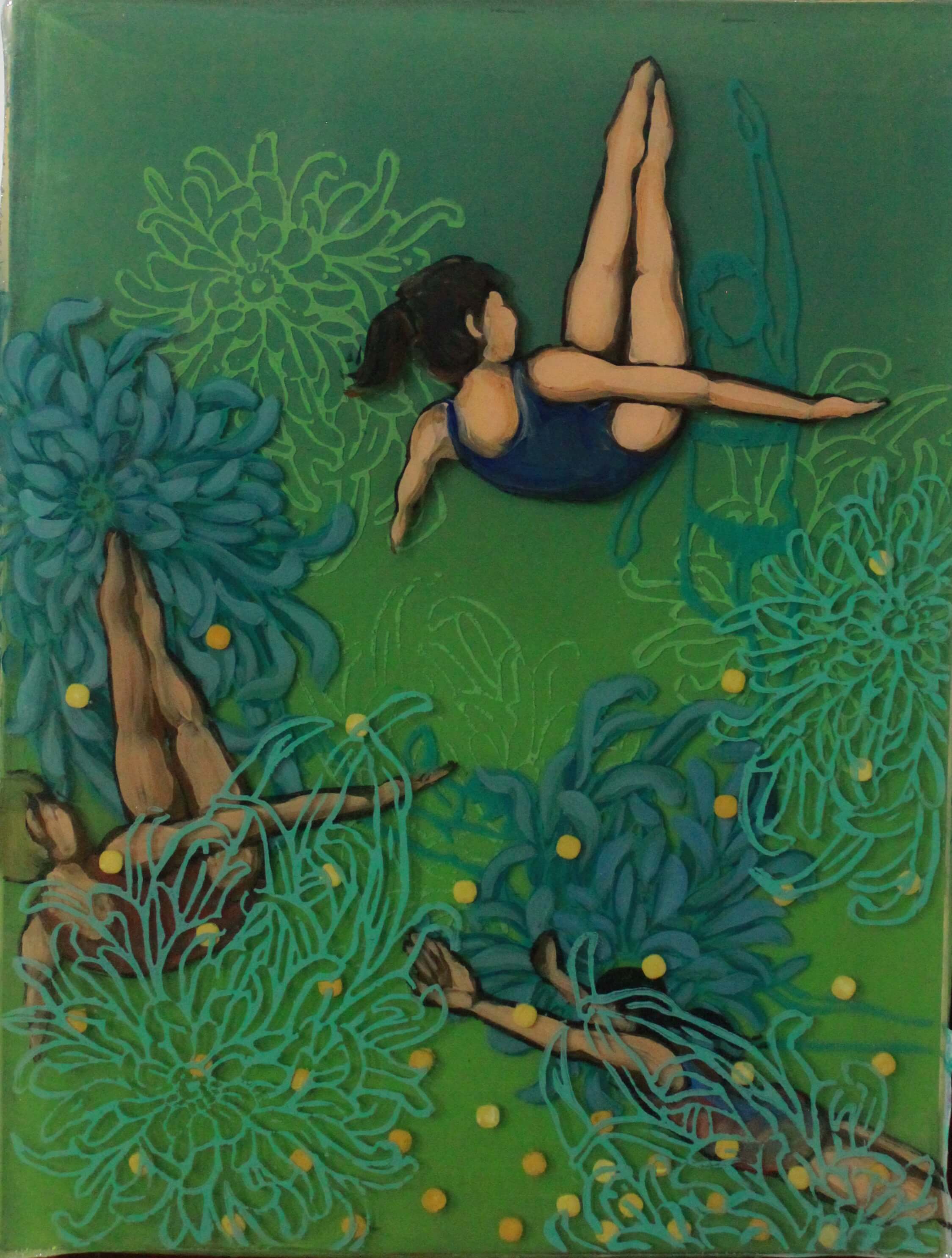

David Perry, Side Effects and Contraindications, 2008

I wonder if I’ve been changed in the night? Let me think. Was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I’m not the same, the next question is “Who in the world am I?” Ah, that’s the great puzzle!

—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Monika Lin’s Double Happiness paintings are generous and generative works that immediately attract the eye with slick surfaces, bright forms, and canny gestures toward the decorative arts, creating a mellow post-Pop buzz while initiating a complex series of associations that work to destabilize aesthetic pleasure and set our assumptions on conceptual edge. We experience a space of simultaneous play and suspension, quickness and freeze-frame, release and capture in the paintings, whose package-shiny surfaces, candy colors and mutating motifs, quickly move beyond the declared object of criticism—the relationship of the individual to the psychiatric-media-industrial complex—to raise unsettling questions about identity, consciousness and the self.

Double Happiness does indeed question the role psychopharmaceuticals play in contemporary America, with its volatile mix of micromanaged social controls and undermanaged “free” markets. But the series’ greater success lies in the speed and ease with which it exceeds the topical issue of pills and advertising and gets at fundamental matters concerning the nature of self and consciousness in a world that—due as much to drug designers’ increasing facility with the manipulation of brain chemistry as to that of marketers and advertisers with consumer perception—often seems to be racing to meet a theorized “post-human” event horizon: that moment where we alter our makeup to a degree that, like young Alice, we risk not quite recognizing ourselves one fine morning when we get out of bed.

Despite the pull of such weighty matters, the works remain light. They are notable for their play: the world of childhood play, invoked by go-kart boys and swinging girls as well as sailing ships and humming birds that hint at dream and fairy tale; the play of light upon fixed epoxy, evoking product packaging, display windows and old TV screens, in which the viewer’s reflected face quite literally becomes, for a moment, embodied in the work; the synaptic interpretive play among shapes, colors and images as the familiar and alien interact, interpretive unpredictability increasing with each repetition/mutation. This multi-level play generates a wealth of possible points of connection among, say, a troop of faceless skipping girls dressed in Eisenhower-era shifts, the chartreuse pills that stream beneath them like digital data, and the enormous lilies and ferns through which the girls skip (or have they, like Alice, shrunken, and if so, what did they eat?).

*

Our best childhood stories delight by way of a fright that teeters on the edge of nightmare. From our earliest years, we seek to cope by, among so many other means, distancing ourselves from them by use of figures, allegories, stories and images. Fears of abandonment, loss of identity and rejection lurk within, sometimes manifesting, through various twists and turns, in works of imagination. Today, of course, they’re as likely as not to result in a prescription, reminding us that the “mind” and a psychoanalysis-based approach to managing its troubles is only part of the story. Our molecular-level makeup—our brain chemistry—is, increasingly, where psychiatry seeks to intervene in the name of happiness and normality for all.

Double Happiness limns the boundary lands between the couch and the lab, teasing out something essential from both the dream state and the pharmaceutical state-of-the-art (and the nightmare realms that shadow them both) without losing the ephemeral and highly subjective delicacy of dream, reverie and hallucination. This light touch extends to the topical object of criticism: Though addressing serious social issues, the works do not judge, condemn or slip into easy pathos or heavy irony; rather, they reveal and represent a singular range of experience that had, prior to their creation, remained badly underrepresented, doing so neither the hermetic code of an intensely private world nor in overdetermined political terms. This work asks us to think through two crucial regions where the private and individual meet the public, corporate and institutional—namely, the mind and the brain.

*

Repetition and reproduction can mean stability and the establishment of identity: a steady beat soothes, an oft-repeated narrative reassures, and habit and routine give shape to lives that otherwise might sink into dissolution or explode into unrestrained mania. Yet repetition also bears with it a distinct horror: the threat of losing one’s identity by being made merely the same as everyone else, of being hollowed out, of the “authentic” self being replaced or altered—that which promises to stabilize identity simultaneously threatens it, trading on the unpredictability of the singularly individual for the comforting fiction of the normatively social.

Double Happiness pursues the terms of this paradox beyond our contemporary moment to touch on points of origin (or at least points of mutation) in the Cold War world of baby boomers and post-boomers. As typical popular representations of the period would have it, the ’50s were Levitt Town and gray flannel suit conformity, a repressive black & white culture that exploded into psychedelic rebellion in the late 60s (fueled, of course, by psychotropic drugs). Lin traffics in the myths of the era (see Dick and Jane play) both to better consider their rhetorical power as enduring myths and to undermine them—take the series title’s evocation of Lin’s Chinese heritage, the gesture toward Chinese painting implicit in the rendering of the lilies, and the changing skin tones and hair colors of the boy and girl forms, which together inject a resistant note of ethnic difference into tableaux populated by stamped white-bread 1950s figures.

In another twist, Lin’s deployment of ironic Cold War imagery evokes boomer tales of lost identity and mindless collective enslavement, both on the big and small screen (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Blob and numerous Twilight Zone episodes pop to mind, not to mention periods of anticommunist hysteria). Indeed, Lin’s biomorphic cellular shapes have an air of sci-fi camp to them, with enormous spiked donuts menacing oblivious go-kart boys or outsized mucosal cell walls engulfing miniaturized little girls. These forms also evoke contemporary biotech and pharmacology, but with a humor and awareness that, again, invites us to connect the dots for ourselves.

One set of connected dots reveals how Double Happiness traces the development of “better living through chemistry” from its earnest and optimistic 1950s and early ’60s heyday through the late ’60s countercultural embrace of psychotropic drugs as a means accessing a radical and transformative subjectivity on into the present, where corporate America has found great success in telling both stories at once, often by way of a cynical irony that acknowledges the failure of both utopian projects—radical individualism and conformist homogeneity—while pushing the promise of personal salvation encapsulated in ever-more sophisticated commodities designed to alleviate, or even eliminate, cognitive dissonance and alienation. Lin’s work responds with an irony of its own, one that, rather than seeking to gloss over contradictions and difficulty, allows them to emerge in clearer terms without indulging in reduction or simplification for the sake of a polemical point. The result is an active and productive ambiguity that springs thought and imagination rather than seeking to contain or shape them. Put another way, it’s an antidote for our heavily mediated and medicated times.

1.Despite Lin’s use of mixed media and assemblage techniques—plaster cast pills and layered epoxy resin here; found objects embedded in previous oil and encaustic works—she definitively considers her works to be paintings. Certainly they function as such, hanging on the gallery wall. Yet they also persistently work to unsettle the category of “painting” in productive ways, for example by combining flatness with a depth created not by tricks of perspective but by working with actual physical depth constructed by transparent layers.

2.It’s worth noting that Walt Disney’s 1951 adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass flopped upon release but enjoyed a wave of popularity as a “head film” at the end of the 1960s along with Fantasia. Disney was so disturbed by hallucinogen-happy hippies’ enthusiasm that the company temporarily withdrew it from distribution.