Nina Mehta Young, Medication and Civilization, 2008

“Man, that inveterate dreamer, daily more discontent with his destiny, has trouble assessing the objects he has been led to use…. If he still retains a certain lucidity, all he can do is turn back toward his childhood which still strikes him as somehow charming. There, the absence of any known restrictions allows him the perspective of several lives lived at once.”

André Breton, The Surrealist Manifesto, 1924

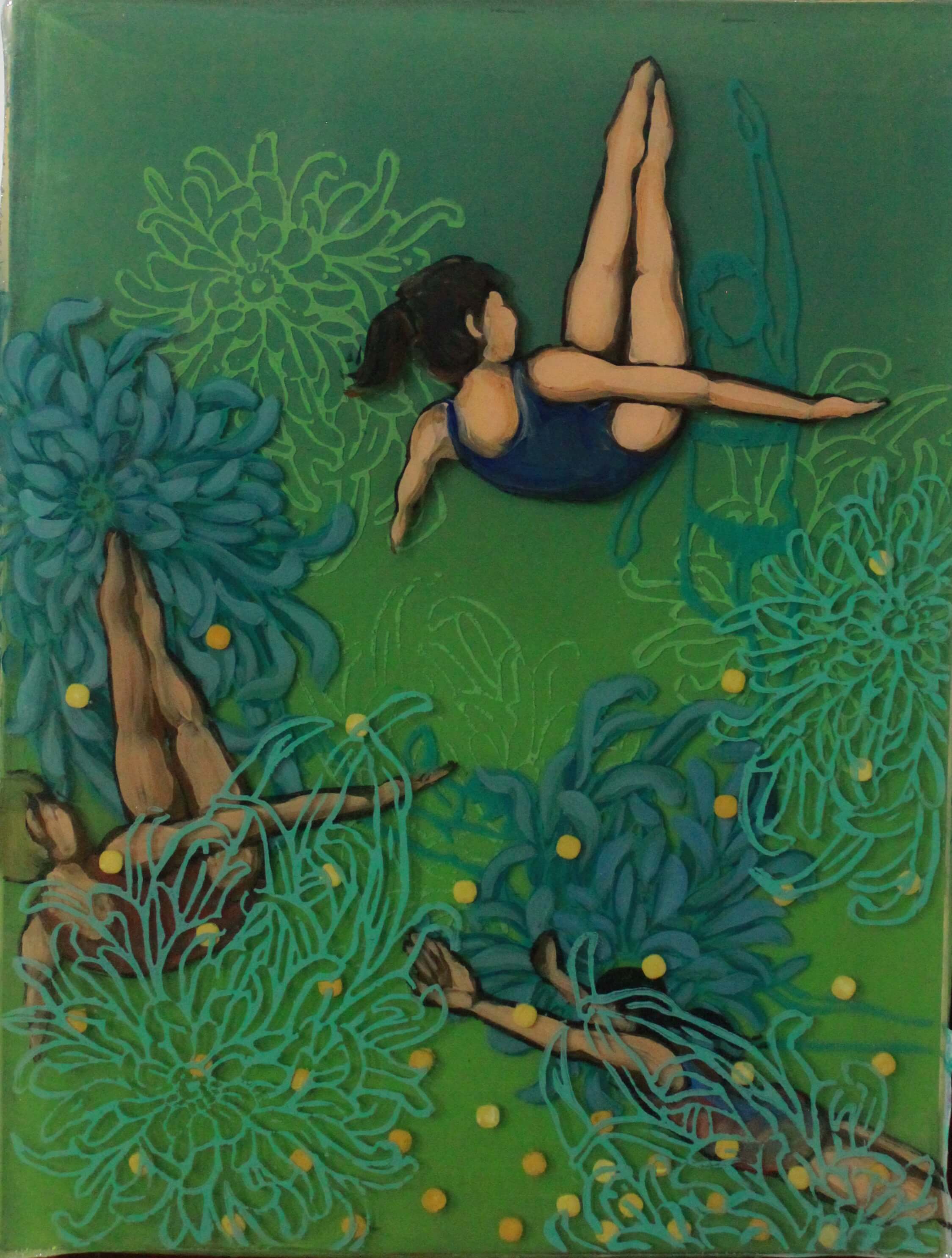

Monika Lin’s Double Happiness images have a dream-like quality. Children race on go-carts past floating biomorphic forms, they skip into a distance of gargantuan flowers, they jump rope in kaleidoscoping fields of magnolia and bursts of dots and capsules that look like a spill on a pharmacist’s table, or a growing culture of cells observed under a microscope. None of these little figures or strange forms are grounded by a defined space, and the effect of a three-dimensional wall-paper is heightened by Lin’s use of transparency: epoxy-resin over arrangements of multiple, colored pills; all of them plaster reproductions of real medicines gathered from the artist’s community, and painstakingly “manufactured” by hand in her studio. The images might be described as hallucinogenic. The connection between the pills, this “effect,” and the care-free children is apparent: While the works convey the visionary freedom and irrational happiness of such a chemically-altered state, they are simultaneously critical of this condition, and the West’s over-use of medication in an attempt to enforce a prescriptive view of normality.

In an artist’s statement Lin states:

“Double Happiness is in part an investigation into our country’s growing dependence on medication as a means towards psychiatric health. The psycho-pharmaceutical industry has broadened its reach to include treatment of mild disorders through prescription medication….motivated by financial gain, the pharmaceutical industry has resorted to the same marketing strategies as purveyors of more conventional consumer items. Through television and print media, the industry has created both a false sense of normalcy in the consumption of and an increasingly frantic demand for psychiatric medication.”

Her images of euphoric children recall the false visions of normalcy, promoted by advertising agencies on behalf of pharmaceutical companies. Her process, obsessively reproducing hundreds of pills, references the mass manufacture and consumption of mood-altering drugs on an industrial scale, as well as “the nature of targeted behaviors and psychologies.” In this context, the images are ironic, the happy children eerily conformist, euphoric, but anonymous, some engaged in the repetitive acts of a “Dick and Jane” reality, some apparently transformed into “super/action children” by their medication. The candy-colored imagery is inviting, yet sinister, colorful, yet claustrophobic; like a tea-party from The Stepford Wives.

This sense of the unnatural is transformed into suppressed hysteria in the hummingbird works where Lin uses the birds to transmit an intense feeling of nervousness and frenetic activity. Here the tiny creatures swarm, imperceptibly beating their wings at a furious rate per second. With their hearts flickering at an unnerving speed, they are an effective metaphor for hyper-activity, or the effects of medication on our organisms – even alluding to the drugs used for one of the most commonly treated conditions in children: attention deficiency disorder.

In “Narrenschiff,” Lin references the artistic and literary figure of the “Ship of Fools,” discussed by Michel Foucault in his “Madness and Civilization.” In Utopian treatises of the Renaissance, the Ship of Fools became the topos for society’s outsiders, cast to the waters, beyond rational society, either until they were ready to re-enter, having come to their senses, or forever isolated in the realm of insanity. In certain versions of the Narrenschiff story, perhaps based on the reality of (certain) actual ships which were used in the Rhineland and Flanders at this time, the merchants and sailors to whom the insane are entrusted also go mad and, their ships continually turned away from safe harbors, are allowed to drift until starvation and death set in (for the crew). Foucault claims that the appearance of the Ship of Fools, both literary and actual, marks the beginning of Western culture’s strict demarcation of sanity and insanity, and that Renaissance definitions of rationality and irrationality foreshadow those of the twentieth century, determining our sense of inclusion and exclusion. Lin updates Foucault, concurring with his critique of Western culture’s over-identification with the scientific and rational, but going beyond his discussion of some of the most controversial techniques in Twentieth century mental health-care, and by casting her “drunken boats” on to a sea of very commonly used medications. Lin’s work suggests that treatment of insanity is no longer exclusively in the realm of institutions and the extreme techniques of the Renaissance, but it is now an accepted part of mass consumer culture.

Double Happiness also recalls the beautiful and ominous environments of the Surrealists, who championed the dream as a key to understanding subjective experience and the human psyche. Although Lin disavows the typically misogynistic attitudes of the Surrealists, she is ideologically aligned with their allowance of “anti-rational” states. For the Surrealists and many other intellectuals of Early Modernism, World War I was the culmination of Nineteenth Century positivism; absolute faith in science, industry and progress, taken to its logical, yet inhumane, apocalyptic conclusion. In contrast to this model, the Surrealists proposed an anti-rationalist vision, where an exploration of, and respect for, the subconscious would make humanity, society and culture healthier. For these artists, the art of the insane was one example of the sub-conscious freed of the constraints of rationality, or the super-ego.

The chemically altered states represented in Lin’s works parallel the dream states represented in many Surrealist artworks, and her questioning of the prevailing attitude to mental health and psycho-pharmaceuticals is analogous to the Surrealist’s critical posture towards rationalism in the aftermath of the Great War. However, Lin’s position is far from the avant-garde vision of the 1920’s. She does not talk as an outsider with an evangelical voice, or propose extreme alternatives. Instead, Lin’s art is both collusive and subversive. It appropriates the language of capitalism; the slick vocabulary of advertising, designed to appeal to the viewer on multiple levels, and employs it with irony to invite critical reflection on a condition that is far more complex than the pharmaceutical companies would have us believe.